THE HOBO CODE: THE SECRET LANGUAGE OF AMERICA’S WORKING CLASS

Ask anyone who lived during the Great Depression, and they’ll share the toll it took on the health and heart. The sudden halt of the economy, which struck on October 19, 1929, — forever known as Black Monday, when the Dow Jones fell 22.6% in one day — was one of the worst, longest-lasting economic devastations in American history. Coupled with a major drought and no farming strategy to combat it, millions of people’s livelihoods, homes, and crops literally disintegrated into dust, and there was no way of telling when it would end or what would be left when it did.

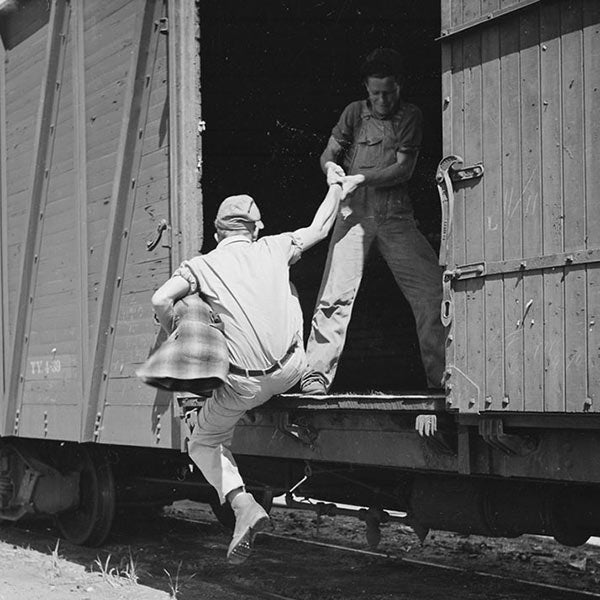

The quivering financial state of the country left many folks with no choice but to abandon their homes in hopes that new possibilities awaited somewhere new. With their families in mind, these nomadic, transient workers and riders of the rails, became known as “hobos”. Though often mistaken for “bums” who had given up and were living on hand-outs, hobos were a different breed: itinerant workers looking for a chance to make an honest dollar, wherever they could find work.

Wandering from place to place and performing odd jobs in exchange for food and money, hobos were met with both open arms and firearms. (People like Al Capone even opened a soup kitchen that served free coffee and donuts to the employed!) From illegally jumping trains to stealing scraps from a farmers market, the hobo community needed to create a secret language to warn and welcome fellow hobos that were either new to town or just passing through. It was called the Hobo Code.

This brilliant, hieroglyphic-like language appeared random enough for busy people to ignore, but perfectly distinctive for hobos to translate. The code assigned circles and arrows for general directions like, where to find a meal or the best place to camp. Hashtags signaled danger ahead, like bad water or an inhospitable town.

It wasn’t just grown men and woman out learning the code. With funding cut, schools were out of session and children were restless. As a way to help their families escape a life of poverty, many 15 and 16-year-olds began adopting the odd job lifestyle. It’s estimated that there were 250,000 teenage hobos zigzagging the rails in America from the late ’20s to early ’40s.

Even though the Hobe Code may have diminished in 1941, we like to think the nomadic worker’s travel code still exists today. Think about all the blogs, reviews, and guides we look at before heading out on a new adventure. They’re the direct descendants of the language invented by those intrepid travelers who spent bleak times wandering America in search of an honest day’s work, a hot meal and safe place to sleep. It’s human nature to help others and add elements of safely when traveling to new places. It’s all about keeping to the code.

Share the most helpful advice you received from a helpful stranger on your travels in the comments below.